“Critical race theory” is being weaponised. What’s the fuss about?

America’s culture war is raging in education

Image: Eyevine/Redux/New York Times/The Economist

“It’s like a bomb went off,” says Christopher Rufo. Mr Rufo himself helped light the fuse. After George Floyd’s murder in May 2020, discussions about racism spread throughout schools, he says. Mr Rufo labelled those discussions “critical race theory” (crt). Controversy around crt has continued to grow—recently expanding beyond race to matters of sex and gender.

With the help of Mr Rufo, now a director of an “initiative” on crt at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think-tank, critical race theory, once an obscure academic topic, became a prominent Republican issue in a matter of weeks. Mr Rufo appeared on Fox News’s Tucker Carlson show in September 2020. “It is absolutely astonishing how critical race theory has pervaded every institution in the federal government,” he said, and was being “weaponised against the American people”. He implored President Donald Trump to issue an executive order banning crt. “All Americans should be deeply worried about their country.”

Suddenly the little-known theory was on the lips of conservative pundits and politicians across the country. Sarah Longwell, a Republican strategist, saw the impact in focus groups. A journalist from the Wall Street Journal called to ask about crt when it was just starting to percolate, she recalls, but she had not heard anything about it. Then, during the next focus group, “it was all anybody talked about”.

Forty-two states have introduced bills or taken other actions to limit crt in classrooms; 17 have restricted it. North Dakota passed its law in five days. School-board meetings have become ferocious. Protesters claim that children are being forced to see everything through the lens of race. The Manhattan Institute now supplies a guide for parents fighting against “woke schooling”, and the Goldwater Institute, another conservative think-tank, provides model legislation. Banning crt in schools was a core part of Glenn Youngkin’s gubernatorial campaign in Virginia last year, and may have helped him win.

And I see this really wild racially segregated, very aggressive, very Maoist training documents…

…that they were using in Seattle. That was an ‘Aha’ moment of discovery for me.

“And I see this really wild racially segregated, very aggressive, very Maoist training documents…”

christopher rufo

Understanding what all the fuss is about requires answers to three questions. What is crt? How widespread is its teaching in schools? And, third, to the extent that it is taught, is this good or bad?

The origins of crt go back to the 1970s. The legal theory stressed the role of “structural” racism (embedded in systems, laws and policies, rather than the individual sort) in maintaining inequality. Take schooling. Brown v Board of Education required schools to desegregate with “deliberate speed” nearly seven decades ago. Yet despite accounting for less than half of all pupils in public schools overall, 79% of white pupils attend a majority-white school today.

Progressives stretched the scope of crt before conservatives did. The theory has spread into concepts like “critical whiteness studies”: read “White Fragility”, by Robin DiAngelo, and you might think white people can hardly do anything about racism without inadvertently causing harm to non-whites. Two years ago this newspaper described the way crt has evolved to see racism embedded in everything as “illiberal, even revolutionary”.

Now Republicans have co-opted crt, also enlarging it to embody far more than its original intent. Mr Rufo brandished it to attack diversity training. “Anti-crt” bills have spread to other topics. “Critical race theory is their own term, but they made a monumental mistake,” says Mr Rufo, “when they branded it with those words.” He proudly recounts how he has used the language as “a political battering ram, to break open the debate on these issues”.

The issues have certainly gained ground. In April Florida’s governor, Ron DeSantis, signed hb7, known as the “Stop the Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees (woke) Act”. The clamps down on the hiring of “woke crt consultants” in schools and universities, and crt training in companies. In June Florida’s education board banned teaching crt and the 1619 Project, a set of essays published by the New York Times that puts slavery at the centre of the American story. The same month a bill in Texas was sold by its governor, Greg Abbott, as “a strong move to abolish critical race theory in Texas”. It bans the 1619 Project and discussions of several race- and sex-related topics in schools.

The anti-crt movement has also begun to worry about the way schools teach gender and sexuality. This includes claims that educators are encouraging children to change their genders. A month before the Stop woke Act, Mr DeSantis signed the “Parental Rights in Education” law, which critics call “Don’t Say Gay”. It prevents discussions about sexual orientation or gender identity in kindergarten through third grade. Mr DeSantis claims both bills prevent “woke” ideology in schools.

More recently, social-emotional learning (lessons aiming to teach pupils non-cognitive skills such as managing emotions and being self-aware) has also been in the firing line. Some claim these lessons are used to indoctrinate pupils with crt.

In other words “crt”, to its opponents, has become code for any action that centres on the experiences of the disadvantaged (including non-white, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people) at work or school. Opponents claim that pupils are being taught that white children are inherently racist, and that white pupils should feel anguish about their skin colour because of their ancestors’ actions. Another complaint is that pupils are being taught to hate America: that by emphasising the arrival of the first slave ship as the true founding moment of America in 1619, rather than in 1776 (as the 1619 Project does), crt-type curriculums focus on America’s faults rather than its exceptionalism.

Is this stuff actually being taught in schools? Some say it’s all a figment of Republican imagination, and call it a witch hunt. “#CriticalRaceTheory is not taught in K-12 schools”, tweeted Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers (aft), a labour union, a year ago. Yet it so happens that both the aft and the National Education Association, America’s largest labour union, have announced support for teaching crt in public schools.

Whether framed as crt or not, educators are incorporating progressive ideas about race, gender and more into the classroom, not least in response to changing demography. In 2000, white pupils were 61% of the public-school population. Now they are 46%. (About 90% of American children attend public schools.) A study from the University of California, Los Angeles (ucla), found that the strongest predictor of whether a district had an anti-crt policy was whether it had experienced a large decrease in white pupil enrolment (10% or more) over the past 20 years. Schools are changing, and so is the discourse within them.

Amy Bean of Scottsdale, Arizona, felt lied to when her principal told her that crt was not taught in her child’s classroom. It was right there in the book, “Front Desk” by Kelly Yang, that her nine-year-old had been assigned. The book focuses on a ten-year-old girl, Mia, whose parents immigrated to America from China, and work and live in a motel. In one chapter, a car is stolen from the motel. Mr Yao, the Asian motel owner, assumes a black person committed the crime. “Any idiot knows—black people are dangerous,” he says. When the police arrive, they interrogate Hank, a black customer, but not others. Later Mia asks Hank about this. “Guess I’m just used to it. This kind of thing happens to me all the time,” he says. “To all black people in this country.”

This passage was not explicitly about critical race theory, but it was clearly about racism and plants a seed about racial inequality. Ms Bean, a self-described conservative, was upset when the principal denied crt’s existence in her daughter’s classroom. She would have liked the opportunity to talk to her daughter about it first or debrief her afterwards, she explains.

Some progressive policies have clearly gone too far. San Francisco’s school board is a notable example. Rather than striving to get children back into schools during the pandemic, it fretted about renaming 44 schools named after figures linked to historical racism or oppression. The list included Abraham Lincoln. Voters fired three members of the board.

There have been other perplexing cases. In 2017 a parent in North Carolina accused a teacher of asking white students to stand up and apologise for their privilege. This was never proved. More recently, public schools in Buffalo, New York, found themselves in a controversy over their Black Lives Matter curriculum. Some say it is anti-white. Others say that the quotes from the curriculum were taken out of context.

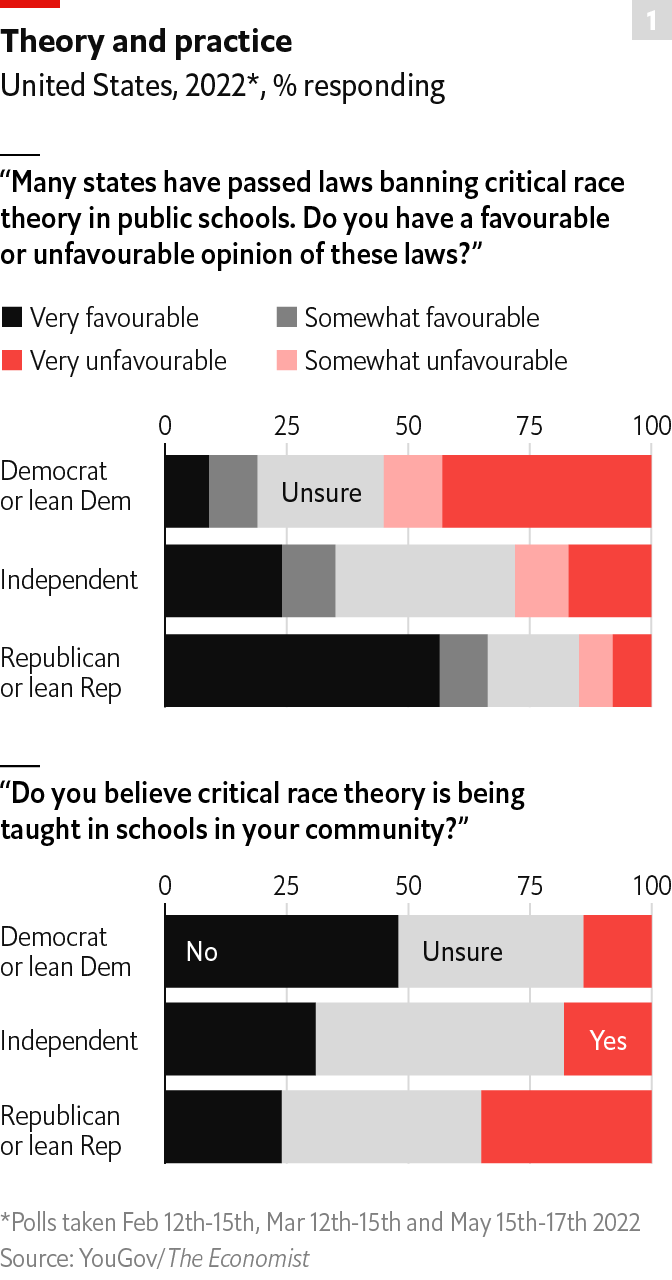

Research and polling suggest that crt, as defined by conservatives, has indeed spread, but is not as pervasive as critics fear. A media analysis by ucla found that 894 districts (representing about 35% of all pupils) experienced a conflict over crt between autumn 2020 and summer 2021. According to a poll by The Economist and YouGov in February, most people do not think crt is being taught in their local schools. Among those asked, 45% claim to know what crt is, and 25% of total respondents have a negative opinion of it. But only 21% think children in their community are being taught it: 14% of Democrats thought so, and 35% of Republicans.

While progressivism may be increasing its reach within schools, crt has hardly permeated state-sanctioned curriculums. American history textbooks are still mostly focused on the accomplishments of white men, says Patricia Bromley, a professor of education at Stanford University who analysed thousands of textbook pages. Recently Florida’s department of education rejected more than 50 maths textbooks (about 40% of those submitted for review) that the state claimed contained crt or the like. Follow-up investigations found little mention of race or crt in them. Curriculums have also grown less political. State standards have become more neutral over time, says Jeremy Stern, a historian at the Fordham Institute, an education think-tank.

What is really happening in schools, then? Largely an increase in availability of one-off courses on racism that pupils can elect to take. Seventeen states have increased teaching about racism and related topics through legislation. Many states insist that African-American or local indigenous history should be taught in schools, though pupils are not required to enrol. Connecticut (where 50% of public-school pupils are non-white) will require its high schools to offer African-American, Puerto Rican and Latino studies from this autumn. The 1619 Project is being taught in many districts despite outright bans in some states. Some changes, however, are mandatory. New Jersey and Washington passed laws last year requiring diversity-and-inclusion classes for pupils or training for staff—the kind of thing that critics see as vehicles for crt.

California is the first state to mandate an ethnic-studies course, beginning with the high-school graduating class of 2029-30. The history course features the experiences of non-white communities (78% of California’s public-school pupils identify as non-white). Two Stanford University studies found that the pilot programme in San Francisco improved attendance and graduation rates for Hispanic and Asian low-achieving pupils. The statewide programme has faced its fair share of controversy. Some Jewish groups felt that it did not focus enough on the Jewish experience or the realities of anti-Semitism. A revised version attempts to plug those gaps. Whether the programme can be successfully adopted statewide is unclear.

I can describe the academic discipline of Critical Race Theory which, in many ways, is irrelevant to this conversation…

…since much of what has been packaged as Critical Race Theory is not reflective of that or even interested in it.

“I can describe the academic discipline of Critical Race Theory which, in many ways, is irrelevant to this conversation…”

kimberlé crenshaw

Is bringing such issues into the classroom a good or bad thing? Americans’ response, as on so much else these days, is polarised. The Understanding America Study, a nationally representative survey by the University of Southern California, found that a majority of Democratic parents said it was important for children to learn about racism (88%), but less than half of Republican parents did (45%).

Many of the schemes described as crt by conservatives (ethnic studies, social-emotional learning) were implemented so that pupils would feel represented in school. Black, Hispanic, Native American and some Asian pupils underperform overall compared with their white peers. These pupils form more than half of public-school enrolment in America.

California’s ethnic-studies programme is one example of how learning about one’s own ethnic history can improve pupil achievement. A study from the University of Arizona also found that participation in a Mexican-American history course was associated with higher standardised-test scores and increased likelihood of high-school graduation. Some researchers and educators consider coursework of this sort to be a key component for improving academic achievement.

If this flavour of crt is beneficial, many pupils will never have a chance to find out. Anti-crt laws have stoked much anxiety. Matthew Hawn, a white high-school teacher in rural Tennessee, was fired for showing a video about white privilege and assigning an essay by Ta-Nehisi Coates, a writer on race relations, to his majority-white pupils. James Whitfield, a black high-school principal outside Dallas, Texas, resigned after being accused of “teaching crt”. (He sent an email offering his school community support after George Floyd’s murder and took part in diversity training.) Some educators fear accidentally defying the law: the language is often vague and the consequences are severe. Punishments can include dismissal, fines or revocation of state funding for schools or districts, and potential lawsuits.

Not all school districts are concerned, though. “Urban districts are not feeling the heat,” says Michael Hinojosa, superintendent of Dallas’s school district in Texas, which is mostly black and Hispanic. “When you get out to the suburbs, that’s where a lot of the vitriol is.”

Many parents of school-age children today attended school in the 1980s and 90s when white pupils were the majority and diversity was less discussed. America has a history of responding poorly to social change in schools. Desegregation in the 1950s and 60s led to violent protests, as did busing—to bring black pupils to white schools—in the 1970s. In 1978, at the time of a growing gay-rights movement, a ballot initiative in California tried (but failed) to ban gay and lesbian teachers.

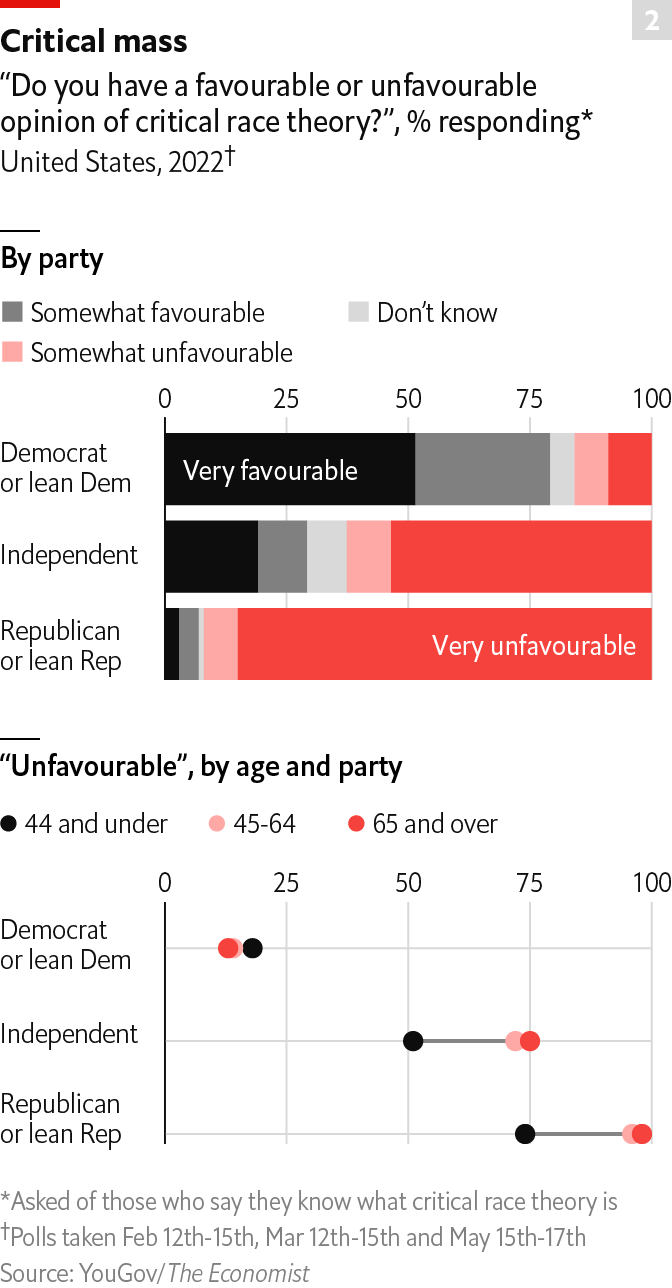

The crt battles could be the latest iteration. And although schools may be majority non-white, voters are older and whiter. The Economist/YouGov polling found that, though Democrats of all ages largely favour crt as a concept, the vast majority of older Republicans and independents dislike it.

Some conservatives see opposition to crt as a way to galvanise support for “school choice”, a policy that allows public money to fund pupils in other public or private schools. The culture wars “could be extremely helpful for promoting school choice”, says the website of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think-tank. Advocates of school choice say it improves options, especially for non-white pupils who often attend under-resourced and under-performing schools. Others claim that school choice is really about racial segregation. The anti-crt movement is about dismantling public schools, says Kimberle Crenshaw, one of the foundational scholars of crt as a legal theory.

The campaign against crt has turned out to be remarkably sticky. “It is putting a name or acronym on a broad set of ambiguous anxieties around changing conversations on race, gender, woke,” says Ms Longwell, drawing conclusions from her focus groups. “crt has become a catch-all for that.” ■

Sources: The Economist